Subscribing to The Christian Century I'm always impressed by publisher Peter Marty's editorials. The one copied below was an eye opener for me. Consequently, I've attached it in it's entirety.

Takk for alt,

Al

The dream and the backlash

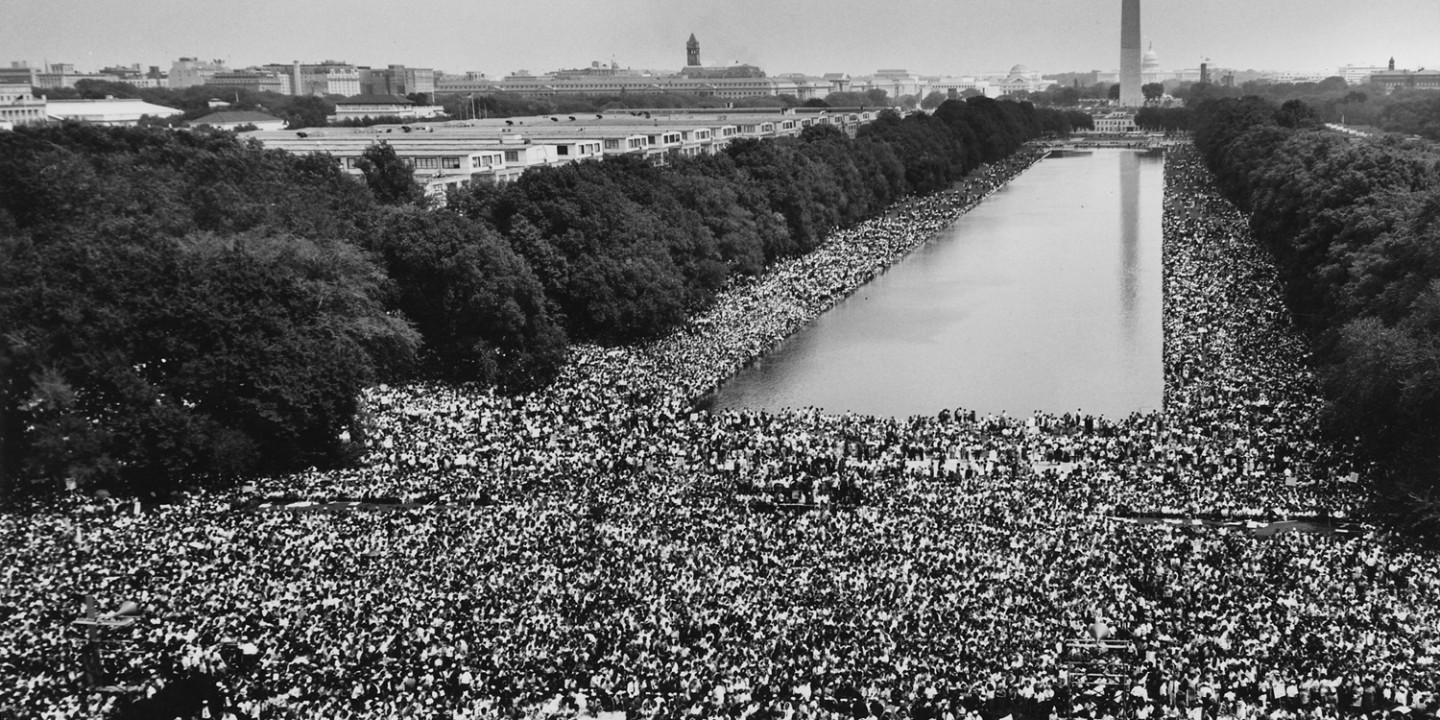

When 250,000 people gathered in the nation’s capital 60 years ago this month, it was the largest demonstration for human rights in US history. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is remembered mostly for the eloquent words of Martin Luther King Jr. which rippled through the crowds of people surrounding the Lincoln Memorial reflecting pool. King’s spellbinding oration, full of optimism for the future, was for the ages.

To many, the day signaled fresh hope that a redistribution of social and economic power might be afoot. It was, after all, a day of social protest for jobs and freedom, not just desegregation or interracial cooperation. “We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation,” declared King. “So, we have come to cash this check.” History books cite the march as playing a role in the passage of both the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

What’s rarely discussed when recalling the throngs that assembled on the National Mall on August 28, 1963, is the nervousness of the White community at the time. Earlier that summer, President Kennedy tried to dissuade organizers from planning the march, calling their effort “ill-timed.” The unfounded idea that masses of African Americans descending on the capital would bring riots and violence along with them prompted businesses to close. Hospitals stockpiled plasma. Liquor sales and baseball games in the District of Columbia were canceled.

Never mind that the only civil rights movement–related violence America had witnessed to date was that which White supremacists had inflicted on nonviolent protesters. Black intrusion into the hub of White political power created anxiety and posed a threat to the dominant culture’s peace of mind.

The word backlash took on new political meaning in 1963. Instead of describing a machine or device that recoils, backlash came to refer to the reaction of White Americans who feared the consequences of Black equality. Cornell University historian Lawrence Glickman says the word “came to stand for a topsy-turvy rebellion in which white people with relative societal power perceived themselves as victimized by what they described as overly aggressive African Americans demanding equal rights.” New York Times columnist Tom Wicker described backlash at the time as “nothing more nor less than white resentment of Negroes.”

Resentment over the pace of new legislation benefiting African Americans created a permanent shift in White political behavior. Pew Research Center studies reveal that in 1958, 75 percent of Americans trusted the federal government to do the right thing most of the time. A majority of White Americans then favored an activist government. According to the American National Election Studies for 1956, 65 percent of White people believed the government should guarantee a job to anyone who wanted one and provide a minimum standard of living. Heather McGhee, who has studied the ANES surveys extensively, notes that White support for these ideas cratered between 1960 and 1964, from nearly 70 percent to 35 percent.

Why the change? The March on Washington proved a turning point. As White Americans witnessed civil rights legislation and federal programs directly benefiting African Americans (and others deemed undeserving), an anti-government ethos emerged. Decades of ANES surveys detail the rise in White disdain for government as Black access to government programs increased. Already in 1966, columnists Robert Novak and Rowland Evans called White backlash “a permanent feature of the political scene.” The US political landscape had changed forever. After 1964, no Democratic nominee for president has won a majority of White votes.

This column appears in the

August 2023 issue. of

The Christian Century

.jpg)